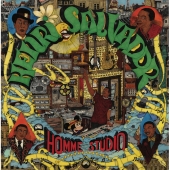

Salvador Henri

Homme Studio

Label: Born Bad

Genre: 60s / 70s Rock / Pop / Progressive / Kraut

Availability

- LP €18.99 Dispatched within 5-10 working days

“Unfortunately, it’s not beautiful songs that make an amazing career. These are songs that will exist after I die.” (1969)

How can one even begin to tell the story of Salvador? Seventy years of music, a thousand of creations of all styles. He has known each and every genre and trend, appropriated some and invented yet new ones. Sometimes associated to ye-ye singers, he’s also known to have brought rock to France (in 1956, with Boris Vian). Yet he’s 26 years older than Johnny Hallyday. He’s 47 when Zorro est arrivé is released in 1964… and 83 at the release of Jardin d’hiver. Seen with today’s eyes it’s all very dizzying. You never know whether he’s young or old, or under which label to file him: jazzman, crooner, entertainer, composer, guitar player, children song singer…

As a kid he picks up the guitar without any theoretical basics and becomes so talented he plays with Django Reinhardt. He learns to sing and compose on his own. The 30s are the years of his training; the 40s of his emancipation within musical ensembles which are to see his talents flourish. He finds his public and perfects his tricks: laughter and seduction. In the 50s he rediscovers the songs of the islands where he grew up, revisits jazz, swing, blues and sings for children. It’s the years of his unforgettable “sweet song”, and his voice changes. His cheeky humour makes way for a multifaceted talent, he fills up venues, surrounds himself with serious lyricists and accumulates classics: Le blues du dentiste, Dans mon île, Syracuse.

“My wife has come to understand me so well that she can now think in my place. When she has an idea it’s, so to speak, my own idea!” (Télé Magazine, 1972)

Jacqueline shapes and emancipates him. When they marry in 1950, she’s a quiet and cultivated young lady who’s to progressively take charge of his career. She enforces her views and frantic pace. A spectator in the world of show business, Jacqueline realises that the artists, left out of professional conversations, often get cheated. Henri undoes the chains binding him to Philps, Vogue, Barclay, his editor, his manager and his impresario, and becomes independent. The Salvadors get to know the inner workings of production, edition, record pressing, distribution and promotion. They always have material to record a demo at hand. Their apartment is full of recorders: one at the bed end for the guitar, yet another in Henri’s office for the Steinway. He’s on all fronts; he accumulates hits, invents, mocks, adapts, and produces.