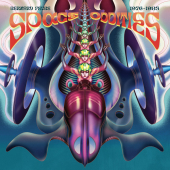

Fevre Bernard

Space Oddities 1976-1985

Label: Born Bad

Genre: 80s Wave / Rock / Pop / Punk

Availability

- LP €22.99 Dispatched within 5-10 working days

You were born in 1946 in Asnières, on the outskirts of Paris. What do you remember from your childhood? Where and how did you grow up, what’s your background story?

One of the first memories I have is my hometown wastelands, we used to play in the mud and have so much fun. Asnières had been spared by the war. My father worked in labor as an assembler in Gennevilliers for the Chausson factory, which belonged to Renault and built engines for buses and trucks. My dad’s parents lived in Burgundy and worked as winemakers and my grandparents on my mother's side made cider in Normandy. My mother was an ironer and a laundress. I grew up in a low-income household with a family who had accounting skills and didn't drink (laughs). I'm an only child.

How did you become interested in music in such a context?

Like other children I went to kindergarten. There was a piano in the playground and I played it with both hands without having learned before. “This isn’t normal, we have to tell his parents,” one of the teachers said. My mother found a piano teacher. I learned to play a bit, to read music, but after a while I got bored because what I was playing wasn't as good as what I would hear on the radio. I thought it wasn't really helpful and I quit.

What were you listening to on the radio?

Originally, I listened to what my parents used to play such as Gilbert Bécaud, Charles Aznavour, Edith Piaf, Les Roses Blanches. But what really made me want to make music was rock'n'roll, and more particularly Afro-American music which I found out about through the Salut les copains radio show, the coolest one at the time, which broadcast on the Europe 1 radio station and took over all teenagers' hearts back then. This is where I drew inspiration from to form a band, Les G Men, which featured Alain Paucard as the lead singer. He brought together a bassist, a drummer, a guitarist and a pianist. We had previously met in a club I used to play in near Saint Lazare. We had a rehearsing space in Montmartre, we were not that good. In the meantime, I got a new, more modern piano teacher who taught in a pricier neighborhood of Asnières. But I still couldn’t see the point of taking music lessons. At the time, I was working in a factory. I had failed in secondary school so I had to enroll in a technical studying programme. After spending three years working in the factory, the boss's son came to me. He had fought the war in Algeria. “Are you bored?” “Yeah,” I replied. “What are you drawn to in life?” he asked, “The only thing I dig is music,” I said. “I know a bar pianist who works in a club near the Champs Élysées. I can introduce you to him if you wish.” I used my blue-collar wage to pay the guy, he would give me lessons every Saturday. He thought it was fantastic to have a worker's son as a trainee. Everything useful in my life I learned from this man.

He had a jazz culture. Then I met Les Vicomtes at the Cynodrome in Courbevoie, they played nothing but rhythm and blues and Ray Charles covers. I took over the pianist's place when he left in order to do his military service.

We performed a few shows at parties but I continued to work in the factory. That is until one day, Les Vicomtes knocked on my door. “We've got a four-month contract to play the Deauville casino,” they said. “How much does it pay?” I wondered. “3700 francs,” which amounted to a doctor's salary. “Let's do this!” I said. When I saw rich people losing tons of money at the casino, it became clear I would always get by with music. I never went back to the factory.

After Les Vicomtes, you played with Les Francs Garçons...

We used to rehearse in the same youth house as them in Courbevoie. I liked their music-hall side and I joined the band as their organist. We recorded two albums and some singles, we put a lot of effort into improving our stage performances. We were the first live band to ever have a stereo, an Italian sound system. This was before 1968, when I started playing electronic organs. It was very analog but required a lot of technique and already involved electricity. I really started getting interested in the so-called “electronic” music by listening to Vangelis, who played along with Demis Roussos in Aphrodite's Child. We Francs Garçons would often find ourselves touring the same cities as them. I would go and see them, and through them I heard a new sound at last. No more guitars and drums! My ears travelled.

Was it a first step towards sound illustration?

It was. From the very moment I became interested in this new type of music, I bought myself some equipment to build a home studio. Around that time, Jean Michel Jarre was around and I thought the same as him. “Since it seems we can't make it, we should produce our own music.” I was passing cassette tapes around to record companies when one day, I got a phone call from Eddy Warner who offered me to work for him. He asked me to supply him with music and he allowed me complete freedom on the matter, with no directions whatsoever.

So it was a day job, but also a space for freedom, wasn't it?

Of course it was. When I make music I dream. I dream that it's going to be great! (Laughs). There's no real process to making music. You can start with a note, or with the lady next door singing in the kitchen. There's a base to it, you have to come up with foundations and from there, you can build up a house. You can go so far as to eventually add the little piccolo flute playing the high notes. To achieve that you need knowledge of the classical orchestra – and it's something I've learned about. Hence, I often hear orchestration mistakes.

Were you interested in science fiction by then?

I was. I was all about having a vision of the future. I'm a bit of a visionary, you see. It has been fifty years I have known about what is coming up. You just have to look and listen. We are in deep shit today because we live in a world where nobody ever looks nor listens.

Did you know any other composers who worked in sound illustration?

No, we had no idea about each other. The publisher made sure we never met, so that we wouldn't consider ourselves as a specific group and think as such. They even orchestrated arguments with musicians I worked with, Jacky Giordano was one of them, in order to maintain their monopoly. I therefore worked on my own. I would provide the music and they would put a title to it. When it came to the cover art, I more or less had my say. We really operated on a craftmanship level.

Alongside your career as a sound illustrator, you also released singles under your own name. Were you hoping to have a hit?

I did indeed, but I always kept it low profile. Unlike most successful artists, I have never been a huge fan of myself. Therefore, I've never tried to fool the audience and steal other people's notes. If I were invited to a show talking about plagiarism, I would have a lot to say.

When you worked in pop music, did you hang out with the showbusiness people?

I hated them! At some point I worked for the Barclay company as an artistic director. Eddy Barclay had quite liked the avant-garde way I had arranged a song by Jean Louis Foulquier – I had done something quite edgy for those times. So he introduced me to lots of people, such as Léo Ferré whom I had dinner with once. He also gave me an office, but I was surrounded by pricks there. The guy next door would spend his time calling his wife on the phone to inquire about how well shirts would sell in their store. They didn't give a damn about music!

Did you start working for the radio at that time?

The director of the Europe 1 advertising department liked the tapes he came across. People would resort to me to solve all types of specific problems, I was a a bit of a handyman. Once, I was entrusted to spice up the Europe 1 broadcast. The point was to make sure listeners would stay alert and not fall asleep for as long as 48 hours and I managed to do so by producing dynamic sound effects and by adding various “tatatas” to the credits.

How did Black Devil Disco Club come about?

My idea was to bring thoughts to dancing people, to have them escape their everyday life. I used disco as a way to have my music enter people's ears more easily. In France, when you offer a record company to listen to something new, the artistic director's reaction is always to go “I can't figure it out.”. Well, you have to learn to figure it out. A lot of songs that have become hits were rejected by record companies in the first place. Music has nothing to do with what they do.

Was the birth of Disco the promise of some sort of a gold rush?

Yes, I took advantage of it. By having people embrace what was below, I made people listen to the surface of the music, what was on top. Disco is what was underneath. It is a simple rhythmic base that I twisted by adding African percussions, as well as Brazilian music and reggae.

With BDDC, did you want to put out a banger and hope to have a hit in the clubs?

I would have loved to. BDDC actually made it to the charts but only thirty years later, when the English digged out the record from oblivion and gave it a second life. I used to go clubbing a lot back then, to dance. You can't really make this kind of music and stay as still as a piece of wood. What I liked about disco was funk music. I liked German disco less than American disco.

What part did Jacky Giordano play in BDDC?

I met him through Alice Sapritch. I was involved in the making of one of her albums, I was her vocal coach. Jacky Giordano was part of it. He was always part of something. His pied-noir personality matched my working-class background and both worked well together, he made me laugh a lot, it was always good fun to be with him. He worked for Pierre Bellemare's publishing company at the time and through him I could have them listen to my BDDC demos. When I needed to come up with English lyrics he helped me write them, then he was mentioned on the record and got paid of course. He acted like a crook, an old habit of his. On this record he was only a lyricist but he ended up being featured as producing the tapes – he was originally supposed to pay for studio sessions, but he never did!

You made a reggae song at the time.

I did, it was Jacky Giordano's idea, as he wanted to capitalize on the reggae craze. I even got invited to a Danielle Gilbert TV show and wore fake dreadlocks as well as a rasta hat my wife had knitted for me. A West Indian backing band played along with me.

In the early 80's, you recorded singles as Milpatte.*

We were joking. Musicians weren't that full of themselves back then. I always make fun of everything, it's part of my character. The name Milpatte comes from when I did music for Gaumont and I worked on silent short films. I played the synthesizer and the piano in the spirit of the 1930's. I would watch the films in the Joinville studio and then compose from memory at home. My fingers would run over the keyboards like a centipede.

How did the British rediscover your music?

The first ones who brought back a song of mine to life were the Chemical Brothers, when they sampled a sound illustration track called “Cosmos 2043” on their album featuring the “Go Glint” song. Aphex Twin then picked up the BDDC album in a car boot sale in England, in 1999. He found it highly innovative and released it as a two-piece on his Rephlex label. When I saw people liked it, I told myself I shouldn't just sit and watch, and I decided to produce 28 after at home. That's when a record dealer named Gwen Jamois (aka Iuke), contacted me and asked if I had any other old stuff I wanted to dig out from my archives. I told him I wasn't interested any more and that instead I looked forward to the future. That's how I got him to listen to the new BDDC, which he thought was fantastic. He then put me in touch with the Lo Recordings people, with whom I've released six albums. I'm currently working on the seventh one.

*Milpatte refers to the phonetics for « mille-pattes », which is French for centipede